Halloween offers a unique opportunity for us to delve into our inner selves, donning identities that may feel restricted throughout the rest of the year, and parading our chosen personas through the streets. This freedom has long been a captivating prospect for individuals in the LGBTQ+ community, transcending generations, and Halloween has evolved into a celebrated holiday within this community. But how exactly did Halloween become synonymous with the “gay high holiday”?

A longstanding tradition connects queer communities to Halloween. Setting aside the clear connection between queerness and the monstrous, Halloween has historically provided a haven where gender nonconformity was not only accepted but celebrated. In the United States, where laws prohibiting crossdressing were prevalent in the 1960s, Halloween served as a rare moment of liberation for LGBTQ+ individuals. It wasn’t until the mid-1980s that courts across the United States began the process of abolishing the criminalization of crossdressing.

Historian Marc Stein, a professor at San Francisco State University, underscores the significance of “carnivalesque” holidays such as Halloween for the LGBTQ+ community.

Related: Texas Secret: Guadalupe Mountains National Park

These occasions disrupt the established social order, providing a safe platform for queer individuals and other marginalized groups to openly express their nonconformity in public, without being perceived as a threat to the prevailing social norms.

“Halloween has always been a holiday where we celebrate unconventional forms of self-expression, the reversal of typical social roles, and the upheaval of social hierarchies,” explains Stein. “For any marginalized community, carnivalesque holidays like Halloween have historically offered opportunities to momentarily assert the potential for a different societal role.” This dynamic is also evident in festivities like Carnival and Mardi Gras.

Related: Sunny Sandler: 5 Things About Adam Sandler’s Daughter

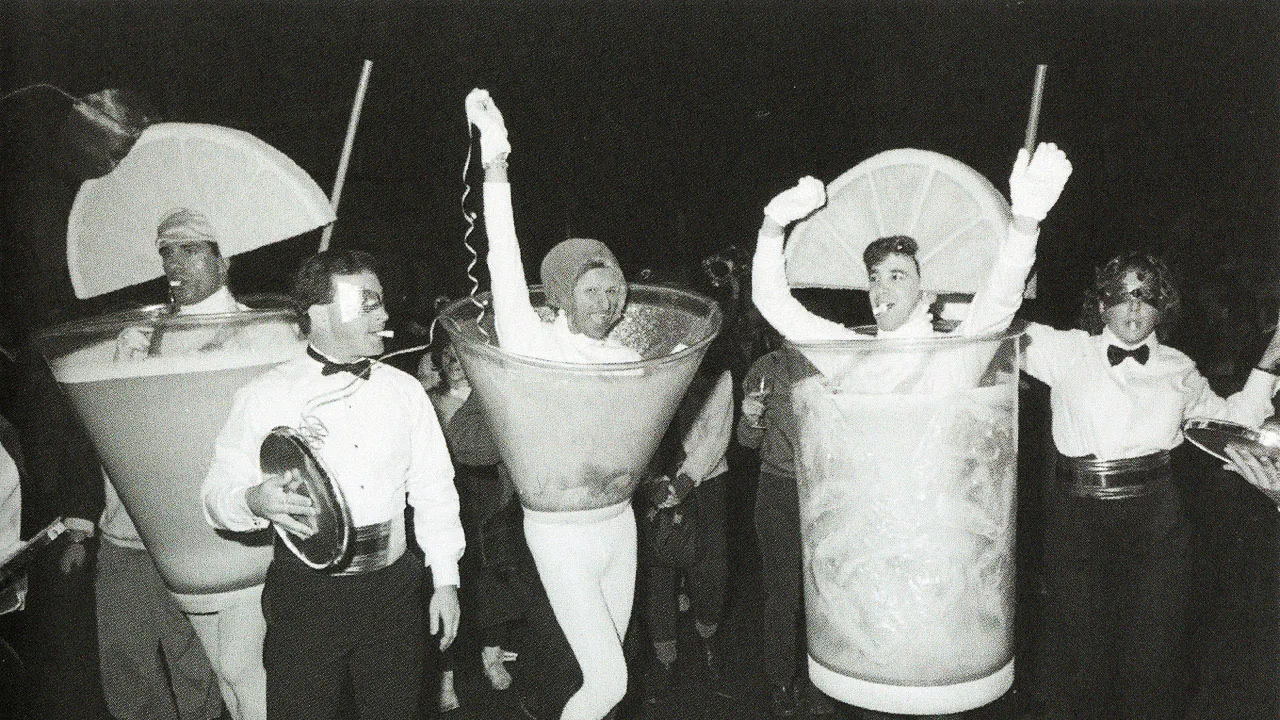

Indeed, the LGBTQ+ community’s affinity for Halloween dates back far beyond documented history. The scarcity of widespread queer media before the mid-20th century makes it challenging to pinpoint the exact origins of LGBTQ+ Halloween celebrations. Nevertheless, as early as 1935, Alfred Finnie, a gay Black man in Chicago, was hosting extravagant Halloween balls on the city’s South Side. These events drew large crowds, as documented by the late journalist Monica Roberts, whose archival research into Finnie’s Halloween drag balls revealed extensive coverage in publications like Ebony and Jet.

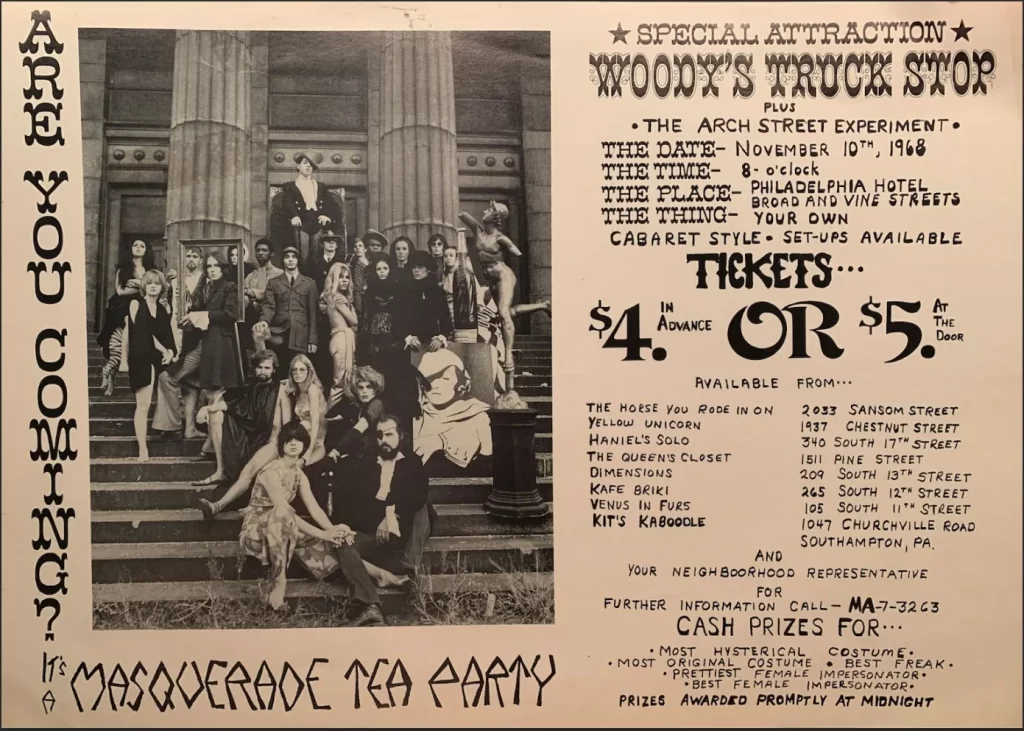

The term “gay Christmas” itself has origins dating back to the mid-19th century. According to Stein, it is believed to have evolved from “bitches Christmas,” a costumed celebration that originated in Philadelphia during the 1950s and 1960s. Queer revelers would trail drag performers from one gay bar to another, effectively creating an unofficial Halloween parade.

Stein points out that due to racial segregation in mid-19th-century Philadelphia, there were actually two “bitches Christmas” events—one celebrated in the white part of town and another in a historically Black neighborhood.

Check our some of our best web stories

Stein clarifies that this was not a case of legal segregation akin to the American South but rather a form of social-cultural segregation that was prevalent in Philadelphia. He notes that several Black individuals he interviewed while writing his book “City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves” expressed feelings of caution and anxiety about participating in the predominantly white gay nightlife in those times.

The celebrations eventually came to an end in the early 1960s when Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo cracked down on alleged rowdiness from both gay and straight participants who enjoyed the event. This serves as a compelling example of “greater visibility leading to greater repression,” as described by Stein. The historian points out that the crackdown on “bitches Christmas” coincided with an increase in press coverage of Philadelphia’s LGBTQ+ communities. While it began as a relatively underground activity, the heightened visibility contributed to the conditions that led to its repression.

Stein also emphasizes that these festivities were not halted due to violations of crossdressing laws, but rather because of business regulations related to drag contests held in bars. “Queer legal repression often relies on laws, ordinances, and statutes that are not directly pertinent but are opportunistically employed,” explains Stein. This approach remains relevant today, notably in the case of anti-drag laws that often utilize vaguely worded obscenity statutes and language concerning the “protection of minors” as a guise for targeting transgender individuals. Many even avoid using the term “drag” to evade legal scrutiny.

While “Bitches Christmas” had a short-lived existence, in the ’70s and ’80s, Halloween celebrations tailored for queer audiences began to appear in major cities. The Greenwich Village Halloween parade in New York commenced in 1973, and Los Angeles’s West Hollywood Halloween parade took off in 1987.

The Greenwich Village Halloween parade boasts its own rich history within the LGBTQ+ community, and Jeanne Fleming, the parade’s artistic and producing director for 43 years, has been a witness to it all. As a long-time resident of New York City, she has been involved with the event since its early days. Alongside her late friend, puppeteer Ralph Lee, Fleming guided the parade through both joyful and challenging times, overseeing its transformation from a neighborhood gathering into a massive event and a cornerstone of the local community.

“The gay community began embracing the parade because it provided a night where you could transform into anything you wished, a time to be open about your identity, which was not as straightforward back then,” Fleming conveys to Them. “What has always resonated with me about the parade is the freedom to be your true self or anyone you aspire to be in your imagination.”

Fleming recalls an encounter with a closeted gay mother who yearned to attend the parade but feared being photographed, as this might inadvertently reveal her true self to her husband and community in Michigan. “Working with her to find a way for her to authentically express herself, free from the fear of being exposed… Those are the types of personal stories I delve into,” Fleming explains. “It’s a remarkable opportunity to assist individuals in being who they aspire to be.”

As Pride celebrations gained momentum in the 1980s, the AIDS crisis reached a critical juncture. Fleming notes that the parade gradually evolved from being an explicitly queer celebration as activists and groups began channeling their efforts into events during the month of June. Nonetheless, the parade retains its identity as a queer space to this day. In its 50th year, the celebration will pay tribute to every contributor to the Halloween parade who has passed away, a list filled with local LGBTQ+ icons, as famously chronicled in Lou Reed’s song “Halloween Parade.” “I personally knew every single one of those individuals,” Fleming remarks, recalling everyone from the “Jesus people” to the “Mayor of Christopher Street” who made their mark.

San Francisco’s LGBTQ+ Halloween festivities also began spontaneously in the 1970s, a development documented by the San Francisco Chronicle. Originally celebrated on Polk Street in downtown San Francisco, the event shifted to the gay Castro District neighborhood in the 1980s. Unfortunately, it officially ceased in 2006 after years of escalating violence surrounding the event culminated in a shooting that left nine people injured.

Mark Kliem played a pivotal role in organizing the Castro Halloween celebration as a member of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a San Francisco-based group of activist drag nuns. They took over the event’s organization in the early ’90s as a means to raise funds for charitable causes. Kliem, known as Sister Zsa Zsa Glamour, recollects, “Once we figured out how to do it, we were able to close the streets at 6 p.m., set up barricades, bring in a flatbed semi-trailer, assemble a backdrop, install lights, and a sound system, and put on a show for two hours, then dismantle it all in a single night. And it was a spectacular performance, it truly was.”

The celebrations attracted crowds to the streets of the Castro, featuring costume contests, drag performances, concerts, and occasionally even fireworks. However, the event was marred by the looming threat of violence, as Kliem explains. “It reached a point where it became too hazardous to be out there,” he says, citing instances of revelers incorporating weapons into their costumes. Reports from the era also documented episodes of anti-LGBTQ+ violence, sometimes directed at the Sisters themselves. Kliem adds, “Some Sisters were being attacked or threatened, so we decided that if they were specifically coming for us as hosts, we wouldn’t participate anymore.”

Despite the closure of numerous revelries over the years, new ones have emerged to take their place. Today, if you’re seeking a LGBTQ+ Halloween party, you needn’t look further than your local gay bar, and cities like Chicago, San Diego, and Provincetown continue to host larger, explicitly LGBTQ+ events.

Amidst this vibrant atmosphere, as Fleming occupies a central role, she shares that the unifying joy of people from all walks of life, whether LGBTQ+ or straight, continuously draws her back year after year. “It’s not about uniformity; it’s about inclusivity,” she asserts. “The concept is to craft a one-night utopia where everyone harmonizes and strolls down the same street together, not just as themselves but as the individuals they aspire to be, you know?”

And what could be more emblematic of the LGBTQ+ community than this?

Related posts:

- 5 Business Hacks Every Entrepreneur Should Know

- Useful Budget Hacks that Will Make Your Life Easier

- Personalizing Your Marketing Strategy and Boosting Your Brand

- Marketa Vondrousova Wins Women’s Wimbledon

- Mark Margolis, ‘Breaking Bad’ and ‘Better Call Saul’ Star, Dies at 83

- Megastar Chiranjeevi: Life of a Cinematic Legend

What's Your Reaction?

One of my friends once said, I am in love with words and a zoned out poser... well, I will keep it the way it has been said! Besides that you can call me a compulsive poet, wanna-be painter and an amateur photographer